The concept of an “open heart” is open to interpretation. Depending on the context, those two words can conjure up thoughts of anything from an early Madonna hit song to a jewelry commercial to a scene in an operating room. There is the symbol and the meaning and the literal meaning—and they are all meaningful. And they are all about the idea of taking the risk, being accessible, susceptible, unguarded, understanding that in order to let something in you must create an opening for it.

In this episode entitled, My First Open Heart, we open ourselves up to the possibilities. We hear from Doctors Paras Shah and Pranay Sinha, and cardiac patient Jacqueline Jackmond, who have either witnessed or experienced first-hand the incredible power of vulnerability; how by exposing ourselves to the whims of fate (and the marvels and limits of modern medicine), we can often find our strength, our purpose, and our love.

P.S. AFTER you listen, this is how a temporary tattoo becomes permanent. (Congratulations again, Pranay and Anne!)

This is the transcript for Episode 10 of the medical and med school podcast, My First Cadaver. Enjoy!

MED SCHOOL TUTORS AD:

My First Cadaver is sponsored by Med School Tutors.

SCARECROW: "Tin Man, what's the matter?"

TIN MAN: "It's Valentine's Day and I've got no heart. We've been on this journey to stop the Wicked Witch, but all I can think about is that nobody's waiting for me back home."

SCARECROW: At least you have a brain! I’ve spent months studying for Step 1, but I can’t figure out what these questions are asking.

MUNCHKIN: Why don’t you try Med School Tutors?

SCARECROW: Who said that?! Dorothy?... Toto?

MUNCHKIN: Down here, you straw schmuck. Their 1-on-1 tutoring will break down what isn’t clicking for you. They make study schedules that chart a clearer path than the yellow brick road. And MST is always hiring tutors -- if you crush your exam, they’ll reward you better than the Wizard himself.

SCARECROW: I guess the Oompa Loompa really are famous for their wisdom.

MUNCHKIN: I’m a munchkin, you burlap bigot!

SCARECROW: Let Med School Tutors be part of your origin story. Together, we can save the world!

EPISODE 10:

FAITH AERYN:

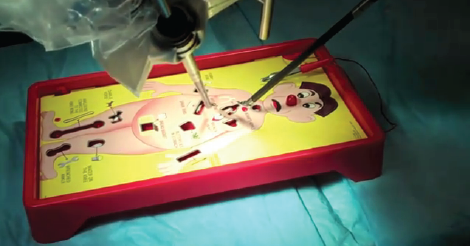

Did you play “Operation” as a kid? I remember the game being all about focus, control, and steady hands, not unlike actual surgery. However, this episode is not about charley horses, rubber bands, and butterflies. We’re talking about open hearts and their many forms in real life. I’d like to do something a little different in our exploration of open hearts for this episode. It’s my pleasure to introduce Miss Jacqueline Jackmond, who can speak from the patient’s perspective of two open heart surgeries.

JACQUELINE JACKMOND:

Two years ago I had open heart surgery. It was to repair the pulmonary valve in my heart because I was born with Tetralogy of Fallot. I think growing up I never talked about it. I just never wanted to admit I had anything wrong, and sometimes it was hard to hide because I have a big scar from the first surgery. It’s certainly not a surgery I remember but it was from when I was a baby to first fix my heart. So there’s this big scar on my chest, and sometimes I’d have to go to the doctor and get a test, and the test would be like a halter monitor test—you have to carry around this big Walkman hooked to your chest with all these wires, and it was kind of hard to avoid that sometimes, and I would sometimes put it away and pretend it was never there. But then, when I came to New York four years ago, I met a doctor, a female congenital heart doctor, and she was the first one to really sit down and tell me about my heart, because I never really cared to learn about it. I just knew something was wrong with it; I knew it was broken. She was the one to bring out a book and tell me the four findings—tetralogy means four, so there’s four different defects. At first I could not remember anything she said because it was all this anatomy stuff and defects, and that triggered me to learn more about it, which I just became very fascinated with. After having some tests, she said, “I need to talk to you, and I think it’s time you start preparing to have open heart surgery.” I was like, “Oh, gosh, this sounds awful, and I guess I just have to do it.” But it also kind of happened at a rough time in my life, because other things were kind of falling apart, like my previous job was falling apart, and I was really not liking New York, so I was like, oh, my gosh, what am I going to do? So I met with the actual heart surgeon and we had a discussion about what to expect and I got to ask my questions, and it was interesting meeting him, because I thought, this is the man who is going to be cutting me open and working on my heart. I wondered what his life is about and what he’s thinking. I’m sure he does this all the time, so I’m sure this is just a snap for him, but it was definitely a big deal for me. So, with tetralogy, one of the main defects is pulmonary stenosis, and that’s a narrow pulmonary valve or a damaged valve, which was definitely damaged over time. The purpose of this surgery was to replace that valve with an artificial valve, because my original one, the one that I was born with, was not functioning correctly, and that caused the rest of my heart to enlarge as well, especially the right side, to pump harder and not work very well. So the main point of this was to replace that valve. I was kind of in the middle of doing all these tests, getting prepared for the surgery, and I had a date scheduled, and my family was going to come out and stay in New York. We had an apartment set up to stay in for a month while I recovered. I got a call from the doctor, and he said, “There’s a chance things might get delayed, so if you want to push up the surgery to tomorrow, I’m free,” which was quite scary. I was like, tomorrow? I’m not even ready, and my family’s not even here, but I felt like it was something I had to get done. That was my only goal: get done, move on with life, get the healing process over with, because I had other things to do, so I said yes. So the next day I went into the surgery, very early in the morning. I went alone; I didn’t have anybody with me. That was kind of daunting, but it was just like, OK, I’m ready to do this. The strangest feeling through this process was the day of the surgery, because I was getting ready to go into the OR, and I actually walked in. I thought first they knocked you out and then wheeled you into the OR. You’re actually very conscious going in there. So I was in a wheelchair, going into the OR, and then just before the doors, they asked, “Do you want to walk in or do you want us to wheel you in?” I said, “I guess I’ll walk in.” And so I did. I walked into the OR and saw the room, and it was actually quite terrifying. I remember seeing the table in the middle, where you lie down, and quite a few people in the room, and the walls are very empty, very white, and everything is just very clean, and—I don’t know, I just saw a lot of white and metal in the room, and that was it. But the doctors and the nurses around the table were there. They were nice. Everything actually happened quite rapidly. I was knocked out not too many moments after that, which was great, because I didn’t want to be awake longer in that room, staring at the things. And then, like a dream, you just go to sleep for a long time and hope that everything goes correctly. Then you wake up and recovery starts. That was really the worst part, the recovery.

FA:

We’ll come back to Jackie in a moment. For now, I want to go to Dr. Paras Shah, a fourth-year resident and graduate of Albany Medical College. Could you describe what actually happens during an open heart surgery?

PARAS SHAH:

Sure. So basically the surgeons make an incision down the mediastinum, the chest wall, and then they have to access the heart so they actually have to crack the ribs open. After they do that, in order to access the heart, which has five liters of blood going through it every minute, they have to put the patient on bypass. That involves creating a conduit between the major veins and the major vessels in the body, such that you can open up the heart without blood spurting in your face. At the same time, since blood isn’t going through the body in the normal way, you have to decrease the metabolic demands of the body, so they lower the patient’s temperature. After that, they use the most fine instruments you can possibly think up to these microscopes, loaded onto their goggles and they make very fine cuts and open up the chambers of the heart. In our case, they opened up the right atrium, which is the chamber that accepts the major vessel, the major vein, the inferior vena cava. We opened up the right atrium, they inspected it and after they cleaned out the atrium or they made sure there were no tumor clots inside the atrium, using very, very fine sutures, very, very slight flicks of the wrist—it’s amazing how they did it—they have to close the chamber back up, such that they don’t trigger much trauma to the tissue because that can cause scarring on the heart. After they’ve closed the heart up, they have to warm the patient back up, which can take up to an hour. I remember that being an hour, just standing there. Then they have to get rid of that conduit, that bypass machine, and reconnect all the circuitry to get the all the blood flowing through the heart, from heart into the lungs, from the lungs to the left side of the heart and then out to the body.

FA:

Oh, man. That’s so intense. When you say “crack the ribs open,” do they actually…are they actually sawing through the sternum? How are they doing that?

P. SHAH:

The ribs are connected to the sternum. Actually the sternum is like cartilage, so they use clippers that can cut through the cartilage. It’s not like a saw, but what I saw, and again, I don’t use these, so I’m not certain, but it was clippers they were using to cut through the costal cartilage, which is not as hard as bone, but not soft as cartilage, which connects the ribs to the sternum.

JJ:

I just remember waking up and feeling like I got hit by a truck. I was in the ICU—tubes coming out of everywhere, my head…tubes everywhere. It was definitely painful. I do remember crying and going, “OK, this is not fun.”

FA:

OK, so here’s the thing we share in your story here, that apartment where you stayed, was not on the ground level.

JJ:

It was the fourth floor, and when I was booking it, the guy was like, if you’re going to have surgery, you probably don’t want to book this apartment. I was like, oh, I can do it. And I was out of the hospital after four days, which is a pretty quick trip to the hospital, then out, and it was around Christmastime, too, so I just made it work. It was very slow getting up those stairs, but I eventually got up there.

FA:

Yeah, but you got up there on your own two feet. Nobody carried you. That’s what’s incredible about this.

JJ:

Yep. I just stayed around there for a few days, and then I think we took a family trip to Macy’s a couple days after that to look at Christmas things. So I was running around a week after the surgery. Out and running about. Well, maybe not running.

FA:

Maybe not running, but mobile. [pause] Now, what good is talking about the heart without talking about one of its greatest capacities? Love. Here’s Dr. Pranay Sinha.

PRANAY SINHA:

In residency, one of the biggest causes of grief is being single or being newly single. I’ve seen both in my friends and I was single for a while. And you know, not expecting anything at all, I walked into this new rotation of mine, and I met Anne. And I think you’re so oppressed by being an intern and being worried about meeting expectations, you barely notice the fact that your supervisor is this phenomenal person and just a gorgeous person to begin with. As time went on, just seeing her interact with her patients was just really just mind-blowing. Gradually, I fell in love with the way she interacted with people and how kind she was. As it happens, this was around Valentine’s Day—so you could say I was a little bit seasonally affected. And I remember she was off on Valentine’s Day, so on the 13th, she gave all these Valentine’s Day cards to our patients, and all the cards had small tattoos in them, the ones that you stick on with water. She wasn’t there the following day, on Valentine’s Day, but her tattoos were there on all my patients. And looking at those tattoos, I realized that I’m feeling funny things for her, and then I think I waited with bated breath for the rotation to end. And within two hours of her supervisory yoke ending, I asked her out and she said yes. And it’s just been phenomenal, and I didn’t think that was going to happen. Here she is actually the boss and the pretty little intern—I never thought I’d be the intern in that cliché, but I literally gave into that.

FA:

That’s terrific. Do you see each other very much in your day-to-day work?

P. SINHA:

Right. Yeah, actually, we do manage to hang out quite a bit. That’s one of the great things about dating someone in medicine, is that they get it if on a night you can’t make it, or you’re just too tired to hang out, or if you’re late—which we both are consistently late to our dates because we just get caught up. And that’s really brilliant. Both of my parents are also doctors, and I see how much of an advantage that is. Because when they have a bad day at work, they come home and they tell each other about it, and when the other person says, “You know, I think you did all you could,” that actually means something. Because if it’s somebody who’s not in medicine, then it’s harder to—you know, even if they’re trying to be nice to you, you’re like, “No, I know you’re trying to be nice, but I don’t think I did.” But when a fellow physician says that to you, you say, “OK, well, I’m glad another professional colleague that I can respect thinks the same way.” That is pretty cool.

FA:

That must be a salve to any gaping wounds from harder cases and things of that nature, no?

P. SINHA:

It is. And I’ll also tell you—this is kind of nerdy—Ann and I often site down and do NEJM cases together—clinical/medical cases together— it’s actually incredibly fun to do that with the person you’re dating and then right after that, we often read poetry. It’s kind of like being able to share your entire self with somebody, not just one side or the other. That’s really cool.

JJ:

Yeah, I think what’s scary about having a heart condition is you’re always reminded, because the heart is an organ you can feel and you hear it, and mine definitely has a funny beat before my recent surgery, and then once the surgery was complete, it had a better sound. It sounds like it functions a little better, but there are definitely rhythms that are off or skipped, rapid, and it’s constant. It’s a constant reminder that this condition is with you forever. All I can do is drown it out with music at night or keep busy during the day. I try not to do anything that would put it at risk, like smoking, or doing drugs or, I don’t know, whatever. Skydiving. [Laughs.] It matters to take care of what you have. Love it. Love it in a weird way. That sounds strange to love it, but I think that’s really all you can do. I think it’s a reminder. I was actually an orphan in a country far away, called Viet Nam [laughs] and I lived in an orphanage with other sick babies, but there were doctors walking through and looking at the different children, and there was one doctor there, and she had spotted me and said, “You know, there’s something different about this baby. She has a heart condition; I can tell.” They could probably tell from my cyanosis—blue fingers and blue lips, because that’s a common symptom of the condition that I had, tetralogy, so just because of the timing of that meeting right there, I was one of the only babies that got out of that orphanage and came to America to have the surgery, and just kind of triggered the rest of my life. That doctor that spotted me had the same condition as me, as well, so I think that probably sparked something in her for me. I don’t know. I’ve obviously never met her again, so I don’t know where she is, but I always think about her. Sometimes my heart still haunts me, the beat of it and the sound and the rhythm, but it definitely is a reminder as well of where I’ve come from and how far I’ve come.

FA:

Personally, I’ve come to believe that in life true strength lies in remaining flexible, vulnerable, and soft—not unlike the heart. What’s more, after the interviews for this episode, I found myself yet again in awe of the heart: its simple efficiency and complex problems, it’s role as the iconic home of our emotions, and the brave physicians who seek to repair it. Rainer Maria Rilke once wrote, “For one human being to love another, that is perhaps the most difficult of all our tasks. The ultimate, the last task and proof, the work for which all other work is but preparation.” And for me, the work doctors do, that urge to heal one another, is one of the greatest expressions of love, it looks like those temporary tattoos had a permanent effect on Pranay. Congratulations.

Thank you to Drs. Paras Shah and Pranay Sinha, and a very special thank you to Jacqueline Jackmond, the My First Cadaver Team, Papa Claire Music and Compulsion Music, our Nerf-blasting friends at Salted Stone, and special thanks to Robert Meekins, who is not a doctor.

P.S. Happy belated Valentine’s Day. We wanted to share this episode a bit earlier, but, alas, real life happens.

And remember, guys: Don’t bring your laptop into the bathtub with you for your browsing pleasure, or you could become someone’s first cadaver.

How do two doctors get engaged? Check out our blog for the next chapter of Pranay’s love story. That’s blogmfc.com